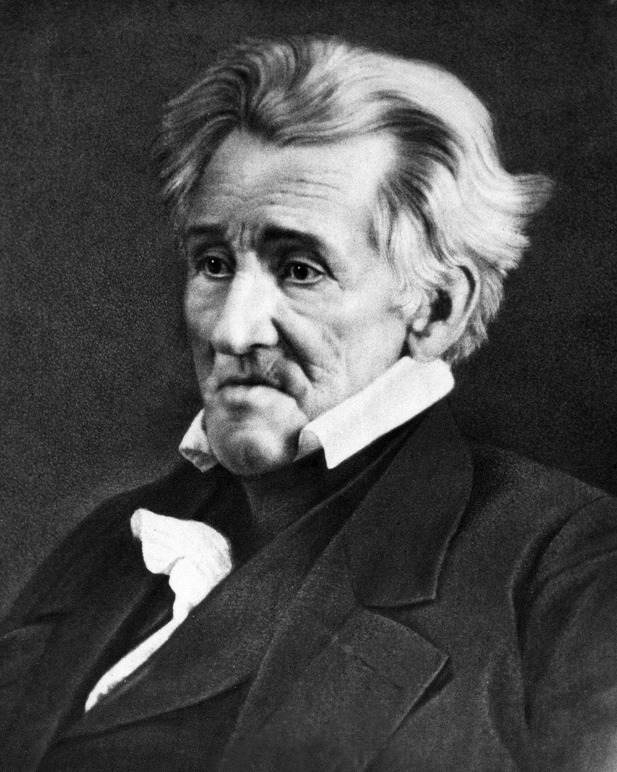

Old Hickory's Finest Hour: Andrew Jackson and Secession

Andrew Jackson was elected President in 1828, when indignation over the federal government's internal improvement programs swept John Quincy Adams out of office. Jackson was expected to be more sympathetic to «states' rights» and to favor limited federal government. However, at a dinner in 1830 commemorating Thomas Jefferson's birth, Jackson gave the famous toast «Our Federal Union — it must be preserved!» — alarming men like his own Vice President, John Calhoun, the states'-rights advocate who offered up his own toast, "The Union — next to our liberty, the most dear!"

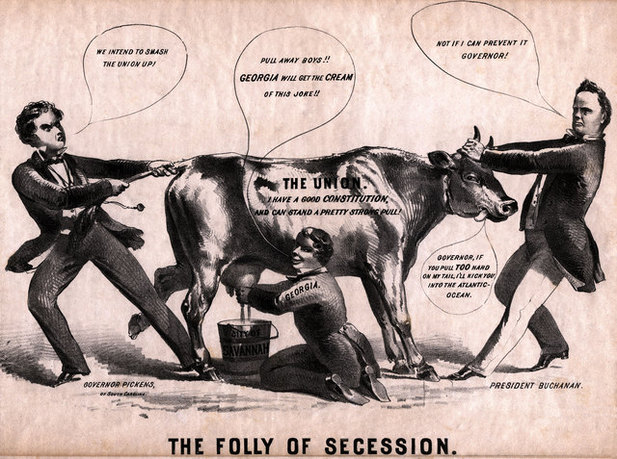

Two years later, Congress passed a tariff bill which President Jackson signed into law. Although this bill was weaker than the one which President Adams had signed in 1828, this did not mollify Calhoun or his home state of South Carolina. With Calhoun's support, South Carolina passed the Ordinance of Nullification, which declared the new law «null» and «void» and threatened that if the federal government attempted to force compliance with the law, South Carolinians would "forthwith proceed to organize a separate Government."

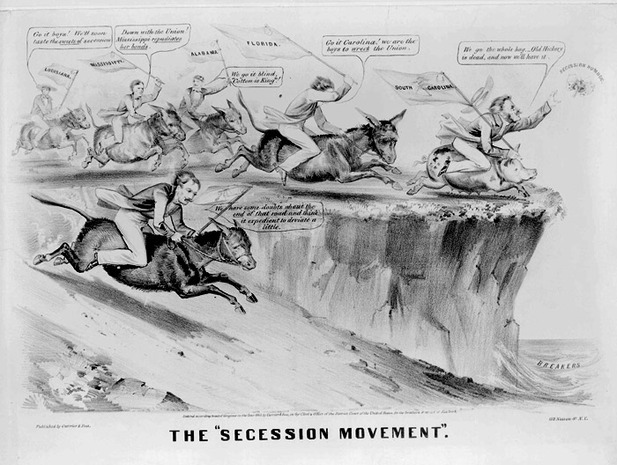

It seemed that all hell was breaking loose. South Carolina politicians insisted that the states reserved the right to nullify laws they thought «unjust», and hurled threats of secession at the Jackson administration. Volunteers were called for to resist the federal government by armed force. As historian Robert V. Remini recounts, «South Carolina rang with a rebel yell» and started striking medals with the inscription «John C. Calhoun, First President of the Southern Confederacy». On «hats, bonnets and bosoms» decorations appeared in support of nullification and disunion. Dispatched to the state by Jackson in anticipation of hostilities, General Winfield Scott exclaimed, «Good God! What do I behold?»

Like Calhoun a Southern slaveowner, Jackson might have been expected to back down — but that was not the way of the Hero of New Orleans. Jackson confronted the nullification issue — and the threats of secession — head-on. «Jackson believed that firmness alone would solve the crisis,» states historian James C. Curtis, and «that any temporizing would only encourage nullification and increase the threat of civil war.»

In a proclamation in December 1832, Jackson declared that the nullification movement was aimed at the destruction of the Union — that it led «directly to civil war and bloodshed» — and that, therefore, it was

incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed.

Jackson insisted that individual states had no right to invalidate federal laws, or secede from the Union, at their own pleasure. He derided «the strange position that any one State may not only declare an act of Congress void, but prohibit its execution; that they may do this consistently with the Constitution; that the true construction of that instrument permits a State to retain its place in the Union and yet be bound by no other of its laws than those it may choose to consider as constitutional.» «Look for a moment to the consequence» of this position, Jackson admonished. If any state can declare a law oppressive and unjust, and therefore null and void — for any reason, however specious — then «every law operating injuriously upon any local interest will be perhaps thought, and certainly represented, as unconstitutional, and, as has been shown, there is no appeal.»

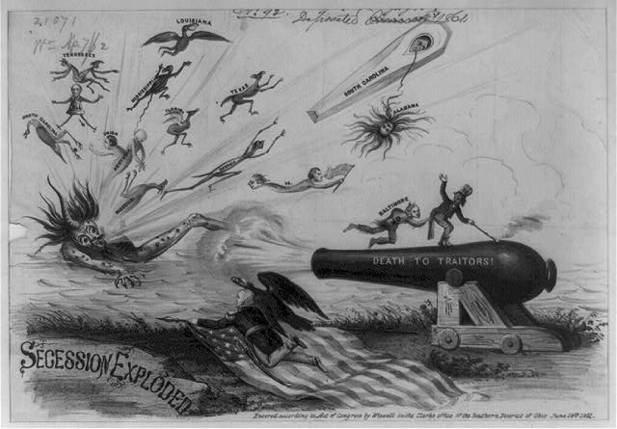

As for secession, Jackson declared that the Union could not be sundered by any individual State, because the Union pre-dated the States themselves. He pointed out that the «decisive and important steps» to declare America a nation were made jointly, not by the whim of separate states. «Under the royal Government» of Great Britain, Jackson reminded us, «we had no separate character; our opposition to its oppressions began as united colonies.… Leagues were formed for common defense, and before the Declaration of Independence we were known in our aggregate character as the United Colonies of America.» Even under the weak Articles of Confederation, the States «agreed that they would collectively form one nation… We were the United States under the Confederation, and the name was perpetuated and the Union rendered more perfect by the Federal Constitution.» Therefore, any State, which constitutes with the other states a Federal Union,

can not, from that period, possess any right to secede, because such secession does not break a league, but destroys the unity of a nation; and any injury to that unity is not only a breach which would result from the contravention of a compact, but it is an offense against the whole Union. To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union is to say that the United States are not a nation, because it would be a solecism to contend that any part of a nation might dissolve its connection with the other parts, to their injury or ruin, without committing any offense.

President Jackson went on to warn, in dark and forbidding tones, the citizens of the state of South Carolina — the state in which he was born. "Disunion by armed force is treason," he declared. «Are you really ready to incur its guilt? If you are, on the heads of the instigators of the act be the dreadful consequences; on their heads be the dishonor, but on yours may fall the punishment.… The consequence must be fearful for you, distressing to your fellow-citizens here and to the friends of good government throughout the world.»

President Jackson's firm stand was met with grateful, patriotic cheers throughout the nation. (Interestingly enough, its sentiments were echoed by one of America's original Founding Fathers, James Madison.) Congress assured Jackson of its approval, and Jackson responded, «if so, I will meet at the threshold and have the leaders [of the South Carolina insurrection] arrested and arraigned for treason.» A compromise tariff bill, sponsored by Senator Henry Clay and acceptable to both Jackson and the nullifiers, made this unnecessary — but Jackson had made his stand, and in so doing, engraved his name in history. As Robert Remini reports, Jackson's proclamation «contributed to a more profound understanding and appreciation of the American experiment in democracy and constitutional government.… His arguments and conclusions provide a complete brief against the right of a state to secede.» These «arguments and conclusions» would later be made by Abraham Lincoln, as effective justification for his successful efforts to preserve our Union.